The Foundations of the Market: A Review of Ropke’s A Humane Economy

Wilhelm Ropke (1899-1966) is a legendary and unfairly forgotten economist and his book A Humane Economy (1958) is literally the best book on economics I have ever read. Influenced by Ludwig von Mises as a young man, Ropke went beyond his teacher to understand the eroding foundations of the free market that was sending Western Civilization in the wrong direction. More than economist, Ropke was concerned with the foundations of the market economy “beyond supply and demand”.

A Humane Economy is divided into five parts the first of which is titled “Reappraisal After Fifteen Years”. In this section, Ropke introduces the book’s theme: “I am the last to deny the importance of external conditions of living as fashioned by technical progress, organization, and social institutions, but the ultimately decisive things for man lie in the deeper spiritual and moral levels” (13); “The decision on the ultimate destiny of the market economy, with its admirable mechanism of supply and demand, lies, in other words, beyond supply and demand” (35).

Part II “Modern Mass Society” is a sort of sociological analysis of the culture at the time A Humane Economy was written. Ropke argues that massive economic institutions like corporations and the state were squeezing out all of the other values that make life worth living: “Is it not, we may modestly ask, part of the standard of living that people should feel well and happy and should not lack what Burke calls the ‘unbought graces of life’ – nature, privacy, beauty, dignity, birds and woods and fields and flowers, repose and true leisure, as distinct from that break in the rush which called ‘spare time’ and has to be filled by some hectic activity? All these are things, in fact, of which man is progressively deprived at startling speed by a mass society constantly swollen by new human floods” (49).

And again: “Once more we return to Burke and his oft-quoted unbought graces of life. The expression occurs in a famous passage of his Reflections on the Revolution in France, where we also find this sentence: ‘But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists , and calculators has succeeded.’ Of what avail is any amount of well being if, at the same time, we steadily render the world more vulgar, uglier, noisier, and drearier and if men lose the moral and spiritual foundations of their existence? Man simply does not live by radio, automobiles, and refrigerator’s alone, but by the whole unpurchasable world beyond the market and turnover figures, the world of dignity, beauty, poetry, grace, chivalry, love and friendship, the world of community, variety of life, freedom, and fullness of personality” (89).

Ropke argues that what he calls the ascendancy of “Jacobin democracy”, the idea that everything should be decided by the majority without limit, is eating away at the foundations of the free society: “This kind of radicalism, typical of a spirit which is not content to accept what is but forever reopen every question, is precisely the mark of mass society and mass man. It is the spirit of men who, together with their social roots, have lost the sense of tradition, principles, and history and who have become the prey of the moment’s whims and passions, as well as the demagogy of leaders translating these whims and passions into ephemeral slogans and inflammatory speeches. Thus modern mass democracy becomes the breeding ground for the revolutionary social religions of our times and the rallying point for the crusades on which the inflamed masses set out to conquer some millennium, some New Jerusalem” (69-70).

In Part III “The Conditions and Limits of the Market” Ropke once again stresses the foundations of the free market “beyond supply and demand”: “We have to admit that the market economy has a bourgeois foundation. This implies the existence of a society in which certain fundamentals are respected and color the whole network of social relationships: individual effort and responsibility, absolute norms and values, independence based on ownership, prudence and daring, calculating and saving, responsibility for planning one’s own life, coherence with the community, family feeling, a sense of tradition, and the succession of generations combined with an open-minded view of the present and the future, proper tension between individual and community, firm moral discipline, respect for the value of money, the courage to grapple on one’s own with life and its uncertainties, a sense of the natural order of things, and a firm scale of values” (98).

Ropke goes on to attack what he calls economism, the idea that the only values are economic ones: “Economism, materialism, and utilitarianism have in our time merged into a cult of productivity, material expansion, and the standard of living, Not too long ago Andre Siegfried recalled Pascal’s dictum that man’s dignity resided in thought, and Siegfried added that although that had been true for three thousand years and was still valid for a small European elite, the real opinion of our age was quite different. It is that man’s dignity resides in the standard of living. No astute observer can fail to note that this opinion has developed into a cult, though not many people would, perhaps, now speak as frankly as C.W. Eliot, for many years President of Harvard University, who, in a commemoration address in 1909, enounced the astonishing sentence: ‘The Religion of the Future should concern itself with the needs of the present, with public baths, play grounds, wider and cleaner streets and better dwellings'” (109).

In Part IV “Welfare State and Chronic Inflation” Ropke addresses “two spreading cancers”: the welfare state and chronic inflation. Of the welfare state Ropke writes: “In an increasingly number of countries it has become the tool of a social revolution aiming at the greatest possible equality of income and wealth. The dominating motive is no longer compassion but envy” (156). And: “The individual and his sense of responsibility constitute the secret mainspring of society, and this mainspring is in danger of slackening if the welfare state’s leveling machine lessens both the positive effects of better performance and the negative ones of worse performance” (163). Finally: “The modern welfare state, in the dimensions to which it has grown or threatens to grow, is most probably the principal form of the subjection of people to the state in the non-Communist world” (171).

Turning to chronic inflation, in the section titled “The Theoretical Background of Chronic Inflation” Ropke mentions the wrongheaded ideas and horrible consequences of John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).

In the next section “The Nature of Chronic Inflation” Ropke pinpoints the cause of our chronic inflation: fiat money and central banking. “It is in the central bank that we have to look for the tap which needs only to be closed firmly to stop the dripping. This fact can hardly be denied, and it puts the ultimate responsibility squarely on the central bank. It is here that all the tangled plumbing converges” (198).

In the final section of Part IV “Conclusions and Prospects” Ropke wrote one of the most powerful and insightful paragraphs I have ever read on modern inflation and I will therefore quote it in full:

The right way of looking at this problem is to regard inflation as an economy’s reaction to a continuous and multiple strain on its resources. It is a reaction to extravagant and impatient claims; to a tendency toward excess in all fields and among all classes; to inconsistent and confused economic, financial, and social policies which disregard all time-tested principles; to the presumption of taking on too much at one time; to the recklessness of always drawing more bills of exchange on the economy than it can honor; to the obstinacy of always wanting to combine what cannot be combined. People want to invest more than saving allows; they claim wages higher than those corresponding to the rise in productivity; they want to consume more than current income can pay; they want to earn more with exports than the latter can yield the economy by way of imports; and on top of all this, the government, which should know better, keeps extending its own claims on the economy’s strained resources. Demands proliferate while the necessary cover of goods is missing. If any man should continually sin against all the rules of reasonable living, some organ of his body will slowly but surely suffer from the accumulation of his mistakes; the economy, too, has a very sensitive organ of this kind. The organ is money; it softens and yields, and its softening is what we call inflation, a dilation of money, as it were, a managerial disease of the economy (217).

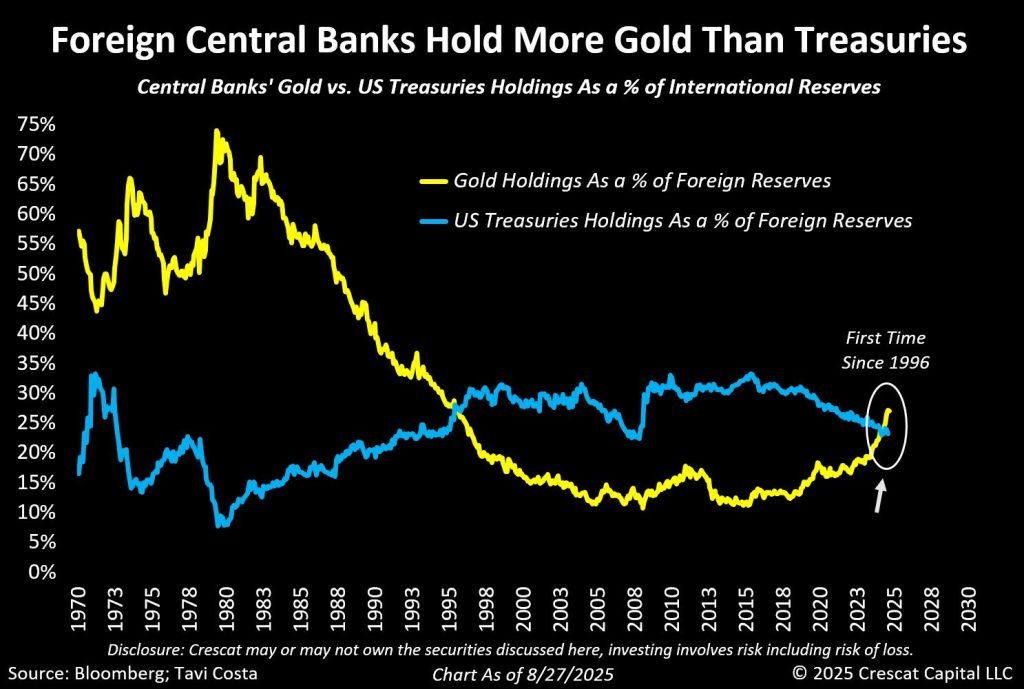

As I read these words my mind couldn’t help turning to the contemporary moment. Austrian Economists like Ropke and Mises have long warned of the consequences of chronic inflation. But things have held together far longer than most of them thought they would. However, with the price of gold exceeding $4,000/oz. and central banks clearly shifting away from US dollar denominated assets and into gold (see chart above), I can’t help but thinking that the jig may be up.

Fiat money was never going to be a sustainable solution because without anything backing it up it is so easy to inflate. That things have held together for so long is hard to explain. But I fear a reckoning, an economic apocalypse that destroys the very foundations of our division of labor economy as paper money tends toward worthlessness as it did in Weimar Germany between the wars when people had to use wheelbarrows to carry all the paper money that was needed to buy things at the grocery store and rushed out at lunchtime to buy what they needed because prices would be higher after work.

In the final Part of the book “Centrism and Decentrism” Ropke tries to explain the difference between the two fundamentally different social philosophies battling for the soul of the world:

On the one side are those who believe that society and economy can be reconstructed from above and without considering the fine web of the past. They believe in radical new beginnings; they are reformers inspired by an optimism that is apparently proof against any failure. On the other side are those who possess a sense of history and are convinced that the social fabric is highly sensitive to any interference. They deeply distrust every kind of optimistic reforming spirit and do not believe in crusades to conquer some new Jerusalem; they hold, with Burke, that the true statesman must combine capacity for reform with the will to prudent preservation (227-28).

We live in an imperfect world but the quest for Utopia often leads to its exact opposite. While the theoretical ideals of Socialism still appeal to many the historical reality of its murderous brutality is undeniable. We have gone a long ways down the wrong road and I hope it’s not too late to turn around and relearn the true principles that have been borne out by history and experience.